MIDAS Memories: 50th Anniversary of the Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak 1967/68

by David Mattey

Health and Safety Executive

HM Chief Agricultural Inspector 1996-2000

1 October 2017

Introduction

This is an extended and updated version of the article originally written in 2015 by David Mattey as a personal account of his experiences during the Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak (FMD) in 1967-68. The original article was intended to form part of a wider project and to prompt other ex-MAFF/HSE colleagues to share their experiences.

In particular it records the specific input of MAFF’s Safety Inspectors/Field Officers beyond their normal role, at a time when FMD restrictions imposed a ban on farm visits. Many of those involved subsequently transferred from MAFF to HSE.

This revised version has again been compiled, to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Outbreak in 1967. David explains:

It reflects memories – of personal involvement, and perceptions – of myself and some of the MAFF Field Officers who were engaged in operations during the 1967/68 Outbreak. As far as I am aware, these have never been previously gathered together. So, 50 years later, perhaps as a memory prompt to others who were involved and for the information of those who were not, a brief scene setting is also appropriate!

Background

There are a few official Reports and references which cover the Cause, Effect and Aftermath of the 1967 FMD. Also separate Reports on the 2001 Outbreak, and links between the two.

- MAFF 1968 – Origins of the 1967/68 FMD Epidemic – “Lessons learned”.

- MAFF 1969 – Report of Committee of Inquiry on FMD (The “Northumberland Report”).

- Wellcome Trust Witness Seminar 2001 – the 1967 FMD Outbreak and its Aftermath.

- National Audit Office – The 2001 Outbreak of FMD.

The contents of these documents are not being explored further here.

To control the spread of FMD (a “Notifiable” disease) The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) operated a national compulsory slaughter/disposal policy, for all infected stock (e.g. cattle/pigs/sheep), plus those within an adjacent buffer area (which were not infected). No vaccination. Control/Restricted areas for movement of livestock were imposed. Routine farm visits ceased – including “Health and Safety” inspections.

The first official case in the Outbreak was confirmed (Virus 01) on a farm in Nantmawr, on the English/Welsh border near Oswestry (Shropshire), on 25th October 1967. Prior to confirmation, the adjacent Occupier had attended Oswestry Livestock Market on that day, with immediate implications on the potential for spread of the disease.

Initial Set Up

The first Outbreak Control Centre was established in Oswestry Divisional Police HQ – a modern complex towards the eastern edge of the town centre. This provided office accommodation for the Centre, a secure vehicle/yard area and a row of garages (and Dog Kennels). It also housed a Civil Defence Control Centre, partly self-contained underground, where a small “Field Ops” centre was established; and a ground level building, which became “The Stores”, for issue of protective clothing/portable materials/hand tools etc.

About 300 yards away, a local garage provided fuel, and a large fenced vehicle park.

Further Centres were set up later as the disease spread North/East, e.g. Chester, Crewe, Ellesmere, Northwich, Macclesfield, Stafford.

The process

Animals showing symptoms were clinically assessed for FMD. Once confirmed, each site was allocated to a MAFF Veterinary Officer to oversee Valuation, Slaughter and Disposal, in-situ. Two systems for Disposal were available – Burial or Burning. Although mass burial in a trench or pit was a quicker/easier option, high water tables on many sites precluded that method. Large numbers of stock were therefore incinerated on linear pyres, which involved massive resource in materials, equipment and manpower.

From memory – a typical pyre took 200 straw bales, 200 railway sleepers, 20 tons coal, 1 ton Foseco (quick burning “coal”) 200 tyres, accelerate – and a match! These could be built and carcases loaded over two days, and fired to burn overnight. Then there was the site clearance…… particularly quantities of the non-combustible tyre wire.

With Disposal complete the site and buildings were disinfected. Farm site activities, especially the Disinfection process, were those where Field Officer (FO) involvement was key.

At peak stage there were some 12 “drafted-in” FO’s regularly on duty at Oswestry on a 7 day week basis. It was winter; the work was physically tiring; protective clothing and strong disinfectant added to discomfort; the environment was stressful, mixed with sympathy for the families on site. But there was an overriding sense of urgency and the importance of the work; plus elements of humour and excitement – which seem common in many emergency scenarios?

Apart from Field Officers, other human resource combined a very experienced group of Vets/Technicians, Admin. staff, Army, Police, Fire Service, Plant/Equipment contractors. Additionally a large “floating” casual labour pool (Wimpey organised) for the manual, and probably more unpleasant, aspects. All part of a major logistical challenge and an overall “Get on with it” approach.

Recollections of events

I was transferred to Oswestry on Detached Duty from Hereford in the first days of the Outbreak – and told to “take enough for a week or so”. After 2 weeks I was allowed a day to go home to restock and return. I had a 3 year old son and a 6 month pregnant wife at that time so they moved temporarily to my home town (Wem) some 15 miles from Oswestry. I could not also take up residence since it would have meant travelling from an infected area to a then “clear” area. We eventually returned home, as the local cases eased some 8 weeks later, in time for the birth of our daughter! I spent the subsequent three weeks “supervising” Milk Tanker decontamination with a transport company operating from a local Milk Factory/Creamery near Leominster.

I arrived as it became apparent that the disease was rapidly spreading and greater resource was necessary; and was assigned to act as contact point for servicing the Disinfection Teams – partly on the basis that I had previous “mechanical” training, but more importantly because I also carried a full kit of tools in my car. We worked from the underground CD Centre, but I was allocated a garage in the main yard from which to provide whatever service I thought necessary! (Labelled “Empowerment” in later times?)

Basically, a two man team equipped with a mobile petrol engine powered pump, applied disinfectant to yards and in buildings on infected premises. The immediate need was to increase the number of teams as additional FO’s arrived at Oswestry.

Additional pumps were obtained, creating a mix of manufacturer and engine type. There was also the problem of water supply and mixing disinfectant. That was resolved by providing a 50 gallon steel drum filling it with water on site as a basic reservoir. Very little use was made of private vehicles so some suitable transport for persons/pump/disinfectant, and sometimes fuel, was vital. I was despatched to Park Hall Camp a Royal Artillery Army base nearby, and “took on” 6 short-wheelbase petrol Land Rovers from the Maintenance Unit. These basic units – with a canvas top, no heater and no power steering – were subsequently delivered to the Centre and allocated to the teams. I also had one as my role developed.

The first week was a bit chaotic – pumps, or rather the engines, required service or repair, or were otherwise unsuitable for some situations (e.g. the Hathaway/Villiers Unit originally designed as a fire pump was ideal for concrete/metal surfaces but lethal in wood/asbestos buildings, and on surface-mounted electric cables! Also the limitations of a unit best described as a lifebelt with a pump and 2-stroke engine in the middle, designed to float/operate on a pond). It was agreed for time/efficiency reasons for me to do minor maintenance in-house.

Consequently, “my” garage contained a supply of common parts from Suppliers, and a couple of spare pumps; and I fixed what I could! Fortunately, the most repetitive problem was over-enthusiastic tugging on weak recoil spring starters, and it was easier to fit a complete spare unit than replace the broken spring on site! That was fixed back at base later, plus oil changes and the odd “spark” issue, to keep things going, and ready for the following morning.

So fewer site and repair visits meant more day time. But that soon changed. I additionally became an emergency “Gofor” – “Have Land Rover/ Will Travel” – delivering petrol and disinfectant to sites, as the odd stand-in for Fire building, towing a generator/lighting unit to sites, ferrying Land Rovers between Park Hall Camp and Centre. Even trialling a Walkie-Talkie radio system – which often didn’t work anyway due to the terrain.

Random light thoughts – and images

Here are a few more random memories:

Staff – I was in B&B with John Woolley, and I also remember Welsh FO’s Roger Kendrick and Ken Morgan being involved. Also Ian Muirden, a local FO, who had been assigned an office role in the main control Centre. Sorry to those I can’t remember/didn’t know then, and who also moved into HSE 10 years later.

Communication – No mobile phones. No Sat Navs. Giving out maps and grid references to places in the Border area which recipients could not pronounce. “Go to Llynclys crossroads and show someone the address” seemed to be common advice.

The WVS Ladies – who provided soup and sandwiches for sale in the Civil Defence Centre.

The casual worker – assigned to “venting” cows stomachs with a long handled Billhook, prior to burial.

The Dart gun – I was asked to deliver a tranquilliser gun kit out to field site where a recalcitrant bullock was defying capture. The user was familiar with its operation and did appreciate that the dart dosage was linked to estimated weight/size, but needed to calm the animal not immobilise it. The animal was much more amenable half an hour later – proudly displaying three darts in its rump!

The mini Ops room underground in CD Centre – Immediately adjacent sat a 1000 gallon emergency water supply tank. I pondered on what might happen to us if it sprang a leak.

After nightfall – a panorama of fires.

Chirk Market – the Police raid which repatriated a large quantity of boiler suits, protective clothing and hand tools, as issued to casual workers.

The Café – a small group of us ate and swapped stories in the evening in the same place. We never seemed to be completely free of the smell of disinfectant especially in the warm. The Owners always made us welcome though, and gave us an allocated table/area.

The Army – The fearsome MU head Park Hall Camp – Warrant Officer II Balls (Yes, that really was his true rank and name!)

The CO of a Junior Leaders Regiment – clad in a long protective coat and wellies, attended a set- up Press event to mark the Troops input to site clearance. To make the point on decontamination a pump operator stood by to hose off his wellies. Over-zealous squirting lifted the coat lower flap and shot disinfectant through the gap. Unfortunately it also revealed that the Officer was from a Scottish Regiment and was wearing a Kilt/Sporran. To his credit he remained wet but unfazed, thus denying the Press an alternative story!

The visiting Vet – Late one Sunday afternoon I was introduced to a Vet from India, who was en-route to Chester. I was to provide him with a Land Rover, give him a test drive, and directions by road from Oswestry to Chester. It was dark and snowy. The garage was shut. The only available vehicle had about a gallon of petrol in the main tank but a couple of gallons in the reserve tank. The Vet was about 5 foot tall and about the same around. Not a shape designed to fit a military Land Rover with limited seat adjustment and a handbrake located horizontally under the thighs. We took a test drive through a deserted town centre – mostly on the pavement on bends/islands (no power steering/poor turning circle). I took him in the direction of Chester and walked the short distance back home. It was only then I remembered that I had not shown him how to switch to the Reserve tank. Curious rather than concerned, I did wonder if he ever reached his destination.

The Tramps/Homeless – Occasionally they were “found” sleeping rough in the Control Area, and treated as potential to spread the disease. The Police brought them into the Centre; they were showered and fed, their clothes/belongings fumigated (in a Dog kennel near “my” garage), and they were released to the wild outside the Area. All one particular man carried in, was a part bag of cold chips.

Fumigation – The ‘enthusiasm’ in the treatment of private vehicles prior to going home. A galvanised bucket, sprinkle of potassium permanganate plus a dash of Formalin, and the lingering smell of Formaldehyde, even with the windows down all the way home.

Commemorative Tie – Upon leaving I was given a tie (designed by one of the Vets); Green with a ‘V01’ motif imprinted. This identified the Virus 01, but the V, set at an angle, also represented the spread of the outbreak North/East from Oswestry.

Health and Safety – I don’t recall that the health and safety of ourselves or private input was considered as a major issue – or even if any incidents/injuries occurred. The situation was unique for several reasons. I am sure that with the introduction of the HSW Act and more sophisticated modern legislation (and indeed other wider organisational controls now), “our” operations just would not happen in the way we experienced.

More recent reflections

I apologised for the “Me” story when I wrote the original article in October 2015, but it was based on my own memories of a very short time span in my career. I am pleased that when I shared it, through ‘MIDAS’ [The Association for ex and still-serving ‘Agricultural Inspectors’ and anyone associated with us] it prompted a few other ex-MAFF/HSE colleagues who were involved, to share their recollections and experiences from working in other Centres and Areas affected through until the containment of the Epidemic and the “all clear” in June 1968.

I thank them all for their contributions to the overall story of our collective involvement in this dreadful episode in farming’s history. Their memories have added to the “behind the scenes” record and I have included them in the attached Addendum.

Thanks also to Alan Plom for his advice and help on presentation.

If anyone reading this has further information to add, please contact me.

Now, where have I left my glasses……… and car keys……….

Addendum to ‘MIDAS Memories – Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak 1967/68’

Additional Feedback from colleagues

Many thanks to those who were able to respond to my draft article with their own memories and contributions to ‘Our Story’ of the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Outbreak. These have now been added to this Addendum to complete the original intention of this “tribute”.

1967 Foot and Mouth Outbreak – Roger Kendrick

Everything you have said brings back memories.

I lodged with my sister in Welshpool but my recollection of the camaraderie we enjoyed would be an understatement. Life was very hard as well with very long days 12 and more hours sometimes.

Driving back from Oswestry to Welshpool at night the whole area was lit up with fires.

You are right about the hardships the farmers went through as well. I went to some farms where the farmers saw their lifetime’s work go down the drain particularly those with pedigree herds. One pedigree pig farmer I went to had sold all over the world and was waiting to complete an order to Russia. I saw farmers crying their eyes out and many would not come out of the house.

The Land Rovers were wrecks. They would not pass an MOT these days. The brakes were awful.

As I was single and lived on a farm I was there from the very beginning and stayed to the very end to help with the close down of the offices. I was part of a convoy that took the Land Rovers back to the Army and it was a race to see who could get there first. One engine blew up in a cloud of black smoke on the way.

I was also delegated to take all the captive bolt guns back to the FMC (Fatstock Marketing Corporation) in Birmingham.

I returned to Welshpool in about the February or so with a few others and helped to fumigate before farmers were allowed to restock. I lived off my expenses – was it £3 a day, for 3 months, and overtime was at time and a half. I think Ian Muirden was in charge of timesheets.

As I said a memorable experience in our life time but not one I would want to repeat.

The 1967 Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak – My recollections – Roger Fronks

On joining MAFF on 07 November 1966 I was posted to the Divisional Office at Gabalfa, Cardiff. On 20 November 1967, all Cardiff Field Officers were, for the first time, restricted to office duties due to the Foot and Mouth outbreak way to the north in the Oswestry area. We were confined to barracks until Friday 1 December. On that day I went home to my parents in Bristol as usual for the weekend but at very short notice I was ordered (by telegram I think) to return to the Cardiff office equipped to be away from home for an indefinite period. On my arrival at Cardiff, FO’s Trevor James, Bill Jones, Dewi Evans, Harry Luke and myself were dispatched to Chester, crammed into Trevor James’s car having been told that official/army vehicles would be provided at the other end and that extraneous vehicles would be a nuisance in an infected area.

We arrived at the Chester F&M Control centre at Dee Hills Park at 15:30. The centre was a hive of activity. The sense of urgency and purpose was palpable. In the control room a huge OS wall map was awash with map pins showing the location of individual outbreaks and the apparent down-wind spread of the epidemic. We were ushered into a briefing room and the Chief Vet and his lieutenants soon swept in looking tired and haggard! I remember vividly that the Chief Vet started the briefing with words – if not exact – to this effect:

“Men!” he said, “This is a bloody business. Those of us who have been here a few weeks are veterans of this hellish conflict. In a few weeks’ time you will be veterans. Now then, I take it that you’ve all brought your cars with you – we need all the transportation that we can lay our hands on.”

When we told him that our contingent had all come in one car he was aghast and ordered us to immediately go back to the place from which we had come and return with our own cars. It was only with great reluctance that he allowed us to stay the night and go back the following day…. we left Chester at 08:15 for Cardiff and I arrived back at Dee Hills Park in my car at 17:40 – a round trip of 320 miles. We went immediately into a Field Officers meeting that lasted until 21:00. A long day!

From then on David Mattey’s description of the process and recollection of events at Oswestry tallies very well with mine at Chester, so I’ll avoid repetition. Notwithstanding our contretemps with the Chief Vet at Chester I agree with David when he mentions that private vehicles were of somewhat limited use. However, my car at the time was a Morris 1000 Pick-Up that I bought brand new (for about £450!) just after I joined MAFF. As a practical load carrier this was seized upon with enthusiasm at Dee Hills Park. I could carry a full set of pressure washing equipment, chemicals, arc lights and anything else that wouldn’t fit into the boot of a saloon car. I could therefore operate flexibly and independent of logistical support. On this basis I enjoyed being a bit of a free agent and, like David, an emergency ‘GOFOR’.

My official diaries faithfully record everywhere I went and everything I did over the ensuing weeks. As the festive season approached there appeared to be little likelihood that we would be allowed home for Christmas but by 22 December the epidemic was coming under control and the work load was easing. As such were allowed to go home provided that we would not set foot on any agricultural premises. This meant that I was prevented from attending our customary family Christmas gathering at my grandparents’ farm in the Forest of Dean

As an aside our family farm was infected during the 1953 outbreak. Our dairy herd and all other livestock were slaughtered. Only the dog was spared. For years after, the dog would disappear and hide away at the sight or sound of a real or toy gun.

A pre-requisite for leaving Chester was that our cars had to be meticulously washed, cleaned and disinfected and then inspected and passed by a vet. The inspection was thorough. The vet would run his finger tip up under each wheel arch and if it came away with a trace of dirt showing the car had to be cleaned again.

I arrived back in Bristol on Saturday evening 23 December and returned to Chester on 27 December. I worked full days on disinfection duties on Saturday 30 and Sunday 31 December – New Year’s Eve. I don’t remember being party to any New Year celebrations.

From 1 January to 04 January the outbreak was under such sufficient control that I was mainly on standby. On 05 January I was released to return to duty at Cardiff.

Foot & Mouth Disease – Lincoln – Brian Slater

I joined the Ministry of Agriculture in 1967; the outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease. An emergency like F&M meant the total abandonment of normal routine, and life got much more interesting for a while! A Control Centre was set up in a local Civil Defence building.

I had a spell operating a plug-and-socket telephone switchboard, then in the F&M Store, the contents of which had not been catalogued. The stocks comprised black rubber wellingtons and waders, long black rubber coats, Sou’Westers, churn brushes and scrapers – everything needed for personal protection (such as it was in those days) and for cleaning up and disinfecting infected farmyards after the stock had gone. After a while the Chief Vet thought there would be more outbreaks, and we stocked up again, but in Lincolnshire there were only five, and we were soon back to normal life again.

Sometimes I was sent to Agricultural suppliers in Lincoln for more brushes, scrapers and the like; sometimes with the Ministry of Agriculture van to deliver supplies to the farms.

It was absolutely tragic coming across the farmers who had lost the results of a life’s work selectively breeding their stock and building up dairy herds – though often you didn’t see them; they stayed indoors, as there was nothing they could do outside, and they could not bear to see the slaughter.

At the beginning, the F&M outbreaks were concentrated where I now live, in the Oswestry area in particular, and all the vets had gone there. At the other side of the country we awaited the arrival of vets from abroad, including Australians and New Zealanders.

But in the interim, on one farm, I found myself supervising the slaughter of a big herd of pigs, after instruction from one of the Ministry vets. The captive bolt pistol was used first, to stun the animal and make a hole in the front of the skull, then a flexible probe was inserted down through the brain to the ‘nexus’ where the spinal cord began. The job was done by Irish slaughtermen. Then the carcasses were tipped into a huge pit along with other animals, all beginning to swell up, and then covered in soil. After a while you just got immune to it all.

On one farm near Cranwell air training base, the ground wasn’t suitable for digging a big hole, and a fire was made, of enormous length. There was a base of straw, then layers of wooden railway sleepers, and then coals. It was Christmas Day. To set it all off, our MAFF Divisional chief acquired a quantity of aviation fuel to set the thing alight. I can’t imagine the Officers’ Mess Christmas Dinner being very savoury, with all the smoke and the smell of all that burning nearby!

Christmas in the Foot and Mouth Centre got quite riotous. There were so many people away from home, and we were on duty throughout without a break – but we did have a party.

Foot and Mouth Disease 1967 – Norfolk – Richard Culpin

I didn’t do F&M, but in 1969-ish there was a suspected case of Swine Vesicular Disease (SVD) on one of my swill-fed pig farms in Norfolk. I helped the vets with initial inspection of the pig’s feet. They did not appreciate being caught and certainly liked less being on their backs whilst being examined for vesicles.

Slaughter, disposal, cleaning and disinfection also took place, and I was involved with checking that a thorough job had been done.

I remember that it was a cold time of year and it was better to help with the work to keep warm.

Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak 1967 – Devon – Denis Welstead

Thanks for that David, I remember it well.

In Devon we were instructed to continue to conduct H&S inspections so that we achieved our monthly safety targets. I managed to do it by visiting horticultural holdings, racing stables and places that did not keep cloven-hoofed animals

Others helped by supervising clean-up operations on farms in the Midlands where cattle had been killed and buried.

Such was life!

Foot and Mouth – Chester – Phillip Gadbury

I was stationed in Brecon at the time. We were sent to Chester.

I was inured to the slaughter aspect having been a former Tech. Assistant in the Animal Health Dept.

I recall that requests for replacement overalls from Contractors reached near epic levels. Also the pressure for them to increase the hours they did on cleaning-down activities.

The hotel opposite ours had a large bar where Welsh colleagues were always in good voice most nights.

Additional information

MAFF FMD film now available

A number of Government and MAFF films have recently been made available on YouTube – including this one on the Outbreak: “Foot and Mouth Epidemic 1967 – archive footage” via: https://youtu.be/zcZ-86M2kAk

NB. About 4 minutes into the film, the eagle-eyed (and older) amongst you might recognise (a young) Roger Kendrick!

Another coincidental link with 1967

Extract from Cumberland & Westmorland Herald: “HSE resuming farm inspection program”, dated Saturday, 26th January 2002:

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has announced that it is returning to a full farm inspection program following a cutback in activity during the foot and mouth crisis.

Roger Kendrick, Principal Agricultural Inspector for the North West, said: “The last 12 months have been a very difficult time for farmers and we have no intention of making things worse during the recovery period. However, preventable accidents continue to occur and we must now get back to helping farmers give a high priority to the health and safety of themselves, their families, their employees and their visitors.”

Health and Safety & the Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak of 2001/02

A comment was made on the absence of any particular mention of the health and safety aspect in my original article. This was probably because there was virtually no appropriate legislation which covered either the workforce or activities in 1967. However, it is worth noting for comparison the changes which had evolved by the time of the 2001 Outbreak.

In 1993 MAFF created a National Health and Safety Manager post, temporarily held by a seconded HSE Inspector. The post was subsequently briefly held on a permanent basis by Dr David Knowles (who originally joined HSE as an HM Agricultural Inspector) and then moved into a new post within MAFF’s Agricultural Development and Advisory Service (ADAS), as Head of Safety and Compliance.

As the 2001 FMD situation developed, ADAS (now privatised) was nominated as the lead on H&S issues. Subsequently, a central on-site H&S Unit with 5 staff was formed, primarily to address the implications of The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999, and effectively centralised control and coordination of H&S activities across all sites. Risk Assessment, Training, and Site Monitoring featured as high priority, given the wide range of personnel and activities across a wide geographical area.

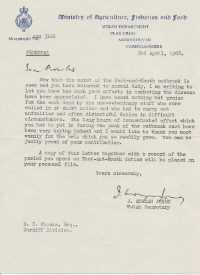

And Finally: Here is the best (and probably the only remaining) official record of appreciation of the efforts of non-veterinary staff in the 1967 FMD Outbreak………

[Click/tap image to enlarge]