J. Russell Brownlie: from apprentice fitter to IOSH President

The path of James Russell Brownlie from a 15-year-old school leaver to esteemed health and safety practitioner would be unimaginable today, taking in national service, a public library and a chance glance at an in-flight newspaper. Add in the decades of voluntary service, an innovative and open-minded approach to jobs in the private and public sectors, and an immense generosity of spirit and willingness to share experiences and knowledge, and Russell’s path to President of the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) becomes easier to grasp.

Russell left Renfrew High School in 1952 at the age of 15, having completed a three-year technical course. He apprenticed with a firm of shipbuilders, William Simons & Company, as a machine engineering fitter until 1955, when National Service intervened, but not before he had completed the ONC course in technical science and engineering drawing at the Royal Technical College in Glasgow.

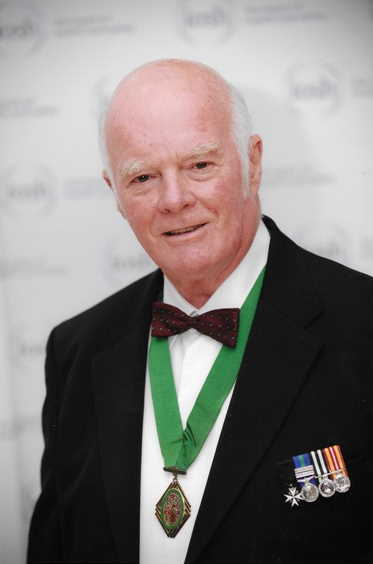

Two years with the Royal Engineers and the Royal Army Medical Corp offered an early indication of Russell’s future career, with the national serviceman seeing active service in Cyprus and Suez with the paramedics in 23 Parachute Ambulance and the third battalion of the Parachute Regiment. Back home, Russell volunteered with St Andrew’s Ambulance before joining the HQ staff and continuing to work voluntarily. The commitment would continue for 36 years, and see Russell appointed an area commissioner for St John Ambulance when his day job took him to Hertfordshire and, eventually, an Officer Brother of the Order of St John.

Planes, libraries and tyres

Returning home from the military in 1957, Russell resumed his apprenticeship with William Simons until 1960 but, with the shipyards already in decline, he looked around for a different job. It was while working as a flight clerk with British Airways (he was used to planes), offloading and boarding passengers, that Russell picked up a newspaper in the cabin and saw an advertisement for a trainee safety officer with India Tyres, part of Dunlop.

Preparing assiduously for the interview, as was his wont, Russell visited a public library in Glasgow. Asking what the library had on accidents at work and health and safety, he was given two leaflets. The librarian asked whether his terms were correct and, following a change of key words, came back with a pile of books, including Heinrich’s Industrial accident prevention: a scientific approach.

Among his interviewers was India Tyres’ managing director, who was on secondment from Dunlop Canada and was involved in the Industrial Accident Prevention Association (IAPP) in Ontario. Recognising Heinrich in Russell’s pledge to halve the accident rate, the MD arranged for the IAPP consultant who dealt with the rubber industry in Canada to look Russell up in Scotland. A month later, the IAPP consultant walked around the India Tyres’ factory with Russell for two hours. “I learned more in those two hours than from any leaflet,” says Russell.

The path to the Presidency

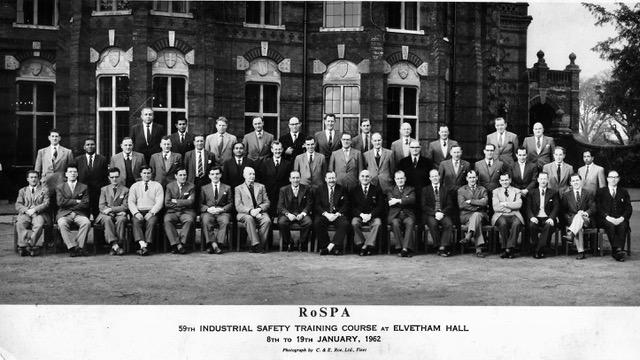

It seemed “logical”, Russell believed, for India Tyres to become a member of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA), which he had first encountered through home and road safety. One year into his job as a full-time safety officer, Russell attended a one-week RoSPA training course. He became an associate member of the Institution of Industrial Safety Officers (IISO), which had initially been a division of RoSPA and would in 1981 transform into IOSH. In 1963, he became a member by examination of the IISO. The exam, he remembers, was in two parts, covering the law and report writing.

In time, Russell became secretary of the Scotland Branch of the IISO and developed his own training syllabus. Fifty years ago, there was a single Scotland branch of IOSH; today there are five branches and sections, with local industrial safety groups, all providing an “effective pool of information”, says Russell. His experience is that there is greater sharing of expertise in Scotland than in England, despite “competition” between the east and west, and that this in part is because it is physically easier for individuals in Scotland to get together. RoSPA Scotland’s Higher Performers Forum is, he adds, an excellent example of what can be achieved.

As IOSH’s Scotland branch secretary, Russell was also the branch’s representative to the national council. During this time, he gained invaluable experience sitting alongside his peers, including the likes of Edwin Hooper, to whom he served as first vice-president for two years. Russell was elected President of IOSH for 1982–83, having been made an IISO fellow in 1979. Russell says his time as President was “challenging” but immensely rewarding, and he always appreciated the opportunity to draw on the considerable experience, generously bestowed, of his IOSH colleagues. He later chaired the IOSH technical board until 1986, as well as the awards committee, which afforded an insight into “what was actually happening” at workplaces.

Russell also succeeded Edwin Hooper as IOSH’s representative on RoSPA’s National Occupational Health and Safety Committee (NOSHC), and the following decade would see Russell bring his long association with RoSPA full circle when he chaired NOSHC from 1994 to 1997. He also served on RoSPA’s board of management and as an accredited safety auditor. The committee, he believes, is “more forward thinking” than many others with which he has been actively involved.

Back to work

After two years at Dunlop, Russell became the regional safety officer for Scotland for John Mowlem in 1963 in order to gain construction experience. It was here that he drew on Heinrich, the Canadian consultant and his own experience to develop his “Four Documents” concept: links with the enforcing authorities, collection and evaluation of information; inspection and correction; training; publicity and service.

Thereafter Russell held various posts, moving from safety officer to safety engineer, safety manager and, by 1980, to group and director level. His employers included ICI, the BBC, the Civil Service Occupational Health and Safety Agency and North Yorkshire County Council. Working for ICI’s petrochemical division from 1969 to 1975, he is particularly proud of introducing a system whereby any lost time accident would trigger a visit to the manager in charge of the operation by the works manager and the safety engineer (himself) to determine what had occurred.

Looking back

In all, Russell has worked for 14 private and public sector organisations. He has had dealt with three fatal incidents, including at employers where, he says, “the systems were generally good”. He has dealt with Legionnaires’ Disease, asbestos and gas clouds on public roads. He has created new group health and safety services, developed policy and practice to reflect organisational change and integrated a risk management culture within diverse organisations.

The principles, insists Russell, remain the same, and a good approach to managing health and safety will suffice whatever the legislative agenda. When the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 came into force, he says there were few difficulties for those that were compliant with the previous legislation as, fundamentally, it “really simplified and formalised what they were already doing” albeit in a goal-oriented way. Similarly, the “six-pack” Regulations in 1992: “If you were compliant before the six-pack came into force, it was not a problem. It did help, however, with organisations that were totally ignorant of occupational safety and health. If you had the four key documents or equivalent, you were fine.”

Looking back, the health and safety world was, says Russell, much smaller. Individual factories would have one or two safety officers and they would meet at each other’s sites, swapping observations and advice that would be “supplemented” by visits from the Factory Inspectorate. In the early days, the link with the inspectorate was straightforward, and he applied the advice from Canada and made contact with the local inspector. There has, in later years, says Russell, “been a change in the inspectorate, with new and younger inspectors less able to strike a balance in the same way”. Regardless, he would tell any safety practitioner and their employer that: “A good relationship and close cooperation with the inspectorate works well.” As do harnessing the support of senior managers, getting out and talking to the workforce and implementing the four documents’ approach.